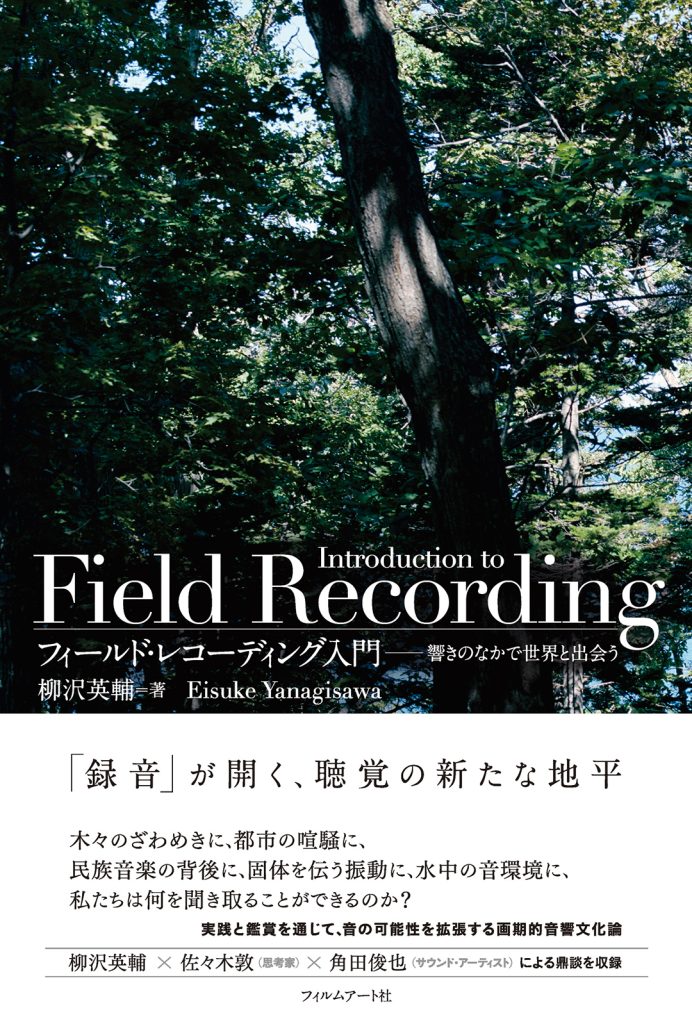

Field recording, which involves holding out the microphone to catch the various ambient sounds outdoors and taking a clip from the soundscape, is attracting much attention. One contributing factor to this trend has been set by Eisuke Yanagisawa (Associate Professor at the Kyoto University Graduate School) who has been engaged in research and writing activities focusing on field recording. His book “Introduction to Field Recording – Encountering the World Through Sound” (Film Art Inc.) which won the 1st “Music Book Award” has created a sensation.

How do we hear ambient sounds and recognize them? Also, how do we take advantage of the methods and concepts of field recording in virtual space? We asked Yanagisawa about auditory sensation in an era of the metaverse.

There are more sounds in the world than those that can be audibly perceived.

─ There may be some among you readers who are not familiar with field recordings. First of all, could you explain in simple terms what a field recording is?

Yanagisawa: The dictionary definition of a field recording is the act of recording sounds in places other than the studio and the product thereof. It has been carried out not only in music but in numerous other fields and was originally a part of academic studies. After the invention of portable recorders, sounds of various ethnic cultures around the world and living creatures became the target of recordings. However, recordings made before studios were created can also be called field recordings from a modern perspective.

─ There are many videos on YouTube explaining the methods of field recordings and it can be said that this field has become the focus of much attention in recent years.

Yanagisawa: That’s right. I feel that the term ‘field recording’ has widely taken root in the last 10 years or so. A great contributing factor is that music production has become digital and anyone can easily take up field recording. The society becoming saturated with visual information, leading people to become interested in auditory information is another factor.

─ It’s true that in the last few years, there have been moves to reconsider the possibilities for voice media. Mr. Yanagisawa, how did you become interested in field recording?

Yanagisawa: When I was in university, I learned an ethnic instrument in Bangkok, Thailand. I recorded my practice sessions on an MD Walkman. When I returned to Japan, I listened to the recording and noticed different ambient sounds in the background. The noise of ceiling fans, the sounds of cars passing by outside the window, the voice of a female teacher I became friends with, etc. There were also voices of children singing along with the piano.

I didn’t notice any of this when I was recording, so when I listened to it upon my return to Japan, I was absolutely flabbergasted! I was astonished to find that by chance, things that indicated the place, time, and atmosphere were vividly recorded. That’s when I realized how interesting field recording is.

─ In your book “Introduction to Field Recording,” you repeatedly mention what makes field recording so captivating is that we are able to see the world from a different perspective through the act of recording and that we are able to capture the world from a whole new angle. What perspective of the world can we capture through field recordings?

Yanagisawa: When you start field recording, we are drawn to objects and landscapes we never took any notice of until that time. To use an example illustrated in the book, I did a recording by placing a Lavalier microphone the size of the tip of a cotton swab into a pipe rolling around at a port. A low sound like drone music was produced. The engine sound of a ship moored nearby resonated and by the amplification of a specific frequency, the result was a low continuing sound. The specific frequency of the sound of waves and seagulls was accentuated, producing a metallic sound.

When you use a Lavalier microphone, you can record sounds of narrow spaces that humans cannot enter and you realize that there are more sounds in the world than those that can be audibly perceived. Based on that concept, even when you are walking around town, you realize that “a different world exists in any minor spot.”

Yanagisawa took part in an album ”Hodokeru Mimi.” A recording from “Hodokeru Mimi,” an event that was held at the Ryosokuin, Kyoto in December 2017.

─ That pipe sound is contained in the album “Hodokeru Mimi.” It portrays a world of extremely mystical sounds. If you hear it just once, you can’t identify the sound.

Yanagisawa: Sounds are often unidentifiable unless an explanation is given. If you see sugarcane swaying in the breeze in a photograph or on video, you can tell some plant is swaying even if you don’t know what sugarcane looks like. However, just hearing a sound doesn’t make it possible to identify what kind of sound it is. Once when I was recording in Minamidaitojima, I played a recording of a swaying sugarcane to some kids and they thought it was the ‘sound of a wave.”

People subconsciously listen to sounds based on their own memory or in relation to various things. Even the sound of an airplane is perceived differently depending on whether it is heard by an old man who has experienced war or a young person who has never experienced war. Sound conveys ambiguous information and that’s what makes it so appealing.

How will technological developments potentially change the act of “hearing?”

─ “Introduction to Field Recording” explains the method for recording sounds (vibrations) difficult for humans to capture both physically and frequency-wise. Through technological developments, sounds that we cannot hear can now be recorded. How do you think technology will change the “way we listen?”

Yanagisawa: It’s true that through technology, we can hear underwater sounds, and the ultrasonic bat calls using a bat detector (*). Human ears can only pick up very limited frequencies, but there are various vibrations in the world that cannot be perceived by humans. Technology has enabled us to experience such existence. I personally have used such tools to expand the act of listening and the world that was previously inaudible has become familiar to us.

- ※ * Bat detector: A device that converts frequency inaudible to humans to one that is audible. It is mainly used for academic purposes in observing and recording ultrasonic bat calls.

Yanagisawa: There are few opportunities for people in general to use such equipment. So I feel that the act of “listening” for people in general will not change in spite of technological developments. In the case of vision, if our eyesight deteriorates, we will get contact lenses or glasses. With hearing, however, we will just get hearing aids. People do not wear hearing aids as much as contact lenses. In that sense, not many tools to augment hearing capabilities have become available.

―Come to think of it, there are no earphones or headphones that pick up inaudible sounds, are there?

Yanagisawa: I think such tools are technologically feasible. But is there much demand? They may capture the interest of artists and creators, but for people in general, that means hearing noises that do not need to be heard, making them unnecessary in daily life.

If I were given a choice, I prefer a function for closing my ears. Eyes can be shut using our eyelids but ears are constantly open 24 hours a day because they do not have the eyelid equivalent. There are earplugs and earphones to close the ears but we do not want to wear them for any length of time because they are uncomfortable. It would be convenient to have an easy on/off function.

― Technology may be used not to augment hearing capabilities but to shut them down. Hmm. That’s an interesting concept.

Yanagisawa: It would be good if a device could be invented which could lower the hearing by 30 decibels without discomfort. It would come in handy when we want to concentrate.

Reproducing the sound environment that is difficult to access through virtual space. The potential for “virtual field recording”

─ What significance do you think the act of “listening” has in virtual space such as in a mirror world or metaverse?

Yanagisawa: I have to remind you that I am not an expert in virtual space. I did some research prior to this interview and found out some information about an “audio metaverse” using a three-dimensional space called the “cube.” There is a virtual space of audio AR inside the cube, making it possible to communicate with people far away. There may be new potential for the world of sound in augmented space.

─ Is there an actual case using the field recording methodology in virtual space? What possibilities exist in this regard?

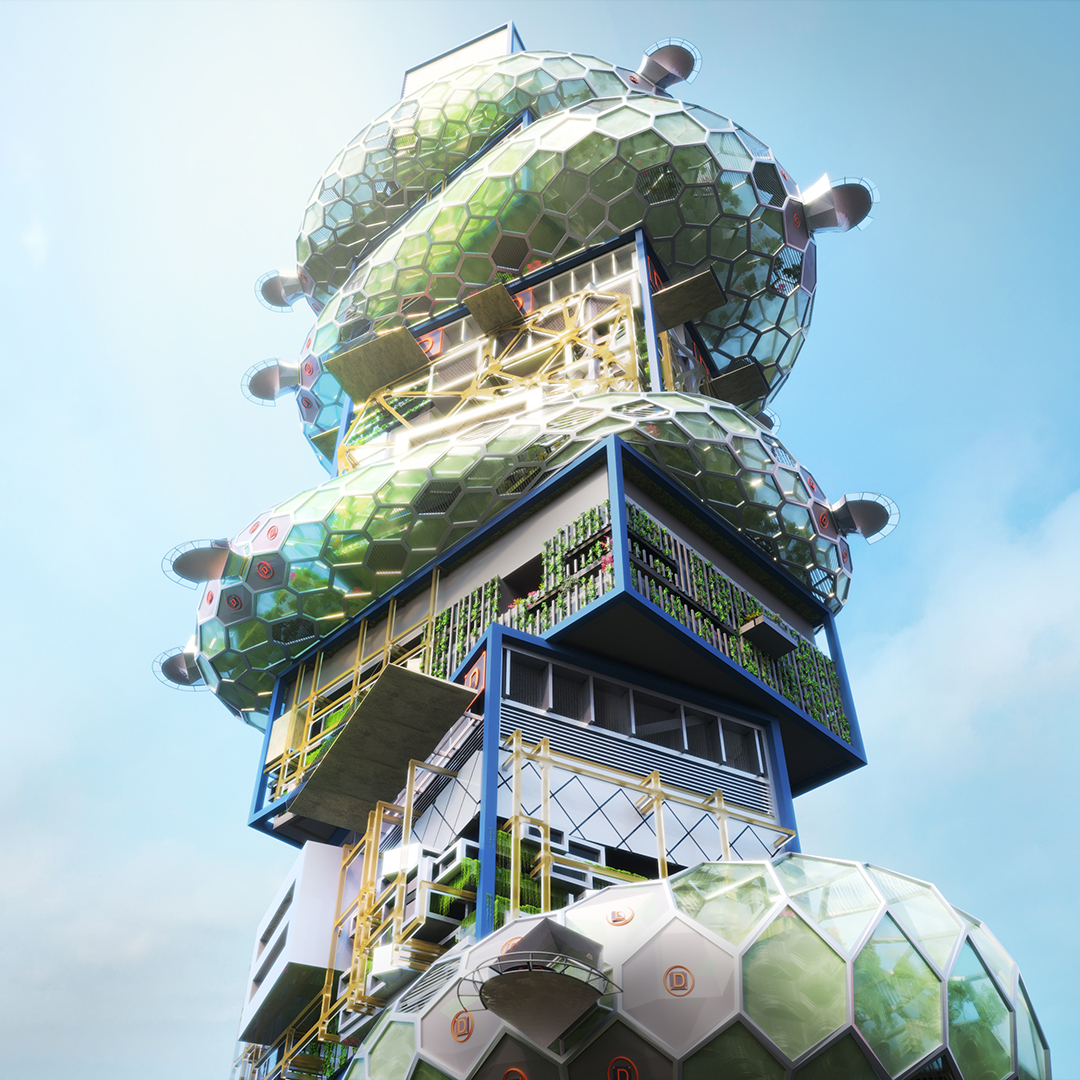

Yanagisawa: I found an interesting case of virtual photography in an article by GEMINI Laboratory (*reference article: What is the World of ‘Virtual Photography’ that Fascinated a Landscape Photographer? We Asked Yuichi Yokota ) A scene from a virtual reality game is cut out and a photograph contest is held. When you think of that, “virtual field recording” is within the realm of possibility. For example, you can reproduce a sound environment of a tropical forest within virtual reality and make a recording by choosing the types and position of microphones.

─ That’s interesting.

Yanagisawa: Field recordings aside, there is potential to create and experience sound environments within virtual space for places difficult to travel to, such as the tropical Amazon rainforest or the Himalayan highlands. In addition, there are possibilities of reproducing realistic sound environments of places for people who have physical limitations and cannot travel are longing to visit so that they can experience it.

Sound is not just emitted in space but echoes and is absorbed as it hits various objects. If you can quantify all of that and simulate it, I think it is possible to reproduce the sound environment.

─ So it is possible to create a sound environment that cannot be captured by human hearing, such as the underwater sound environment of whales, etc.

Yanagisawa: That is a possibility. There are infinite possibilities in that sense, such as being able to experience the world audibly perceived by bats. The method using a multichannel speaker to play sounds stereophonically recorded through field recordings is already being implemented in various places. Perhaps more complex things can be made possible in a VR world.

Can folk music unique to virtual space be created?

─ In “Introduction to Field Recording,” you mentioned that “the subjects have a common interest in sound that is unique to a particular land or location whether it be a cultural sound (including music) or an environmental sound.” Uniqueness in sound is a characteristic of field recording, isn’t it? What significance do you think such uniqueness has in virtual space?

Yanagisawa: Sound that is recorded originates in a particular location and any recording contains sound that is unique to that location. By contrast, sound that is simulated by a computer or a synthesizer sound can be said to have little uniqueness to a particular location.

When a sound in a particular location is reproduced in virtual space, the unique sound source may manifest different uniqueness in virtual space. When that happens, uniqueness in reality may become relative and actual sounds may be redefined.

─ That’s an interesting point. By sound being redefined in a virtual space where little uniqueness is normally found, new uniqueness will be created. Perhaps from such uniqueness, folk music peculiar to virtual space may be created.

Yanagisawa: That may become possible.

─ This is the last question. In modern times, what significance is there in the act of making a recording at a specific time and space and re-editing it?

Yanagisawa: I think talking in the abstract is hard to grasp, so I will explain in specific terms. I think that “this sound in this location” is irreproducible and cannot be substituted. Take for example, trivial conversations with family and friends. If you record such irreproducible conversation and listen to them 30 or 40 years later, there would likely be vividness that cannot be expressed in photographs or videos. Sound contains less information compared to photographs and videos, making it more conducive to stirring the imagination.

I often tell my students, “Record conversations with your friends and listen to them 20 years later. It’s bound to be interesting.” You will lose contact with certain people after 20 years and everyone will have changed. We gradually forget details of any given moment, but we can save sounds connected to memories of people, and not only record but listen to them later on. That’s one fascinating thing about recording sounds at a particular time and playing them back.

Book Information

-

“Introduction to Field Recording - Encountering the World Through Sound”

“Introduction to Field Recording - Encountering the World Through Sound”

Author:Eisuke Yanagisawa Price:¥2,400+tax ISBN 978-4-8459-2124-9

- Related Link:: http://filmart.co.jp/books/art/music/field_recording/

Guest Profile

-

Eisuke Yanagisawa

Eisuke Yanagisawa

Born in Tokyo. Completed Asia and Africa Area Studies Graduate Course at the University of Kyoto. Doctor (Area Studies). Currently an associate professor at the graduate course of the above university. Main research is the sound culture related to the metal percussion instrument ‘gong’ found in central Vietnam. In addition, Yanagisawa has produced recordings and videos focusing on various field sounds and has presented his words in domestic and overseas labels and at film festivals. His main writings include “The Gong Resonates in the Land of Vietnam” (Tokosha, 2019. Received the 37th Hisao Tanabe Award) and “Introduction to Field Recording - Encountering the World Through Sound” (Film Art Inc, 2022. Received the 1st Music Book Award).

- Related Link: https://www.eisukeyanagisawa.com/

Co-created by

-

Hajime Oishi

Writer

Hajime Oishi

Writer

Born 1975 in Tokyo. Writer. His main writings focus on popular music/pop culture from Asia and around the world. His writings include: “South Pacific Song Line,” “Postwar History of the Bon Dance,” and “Visiting Rural Tokyoites.”

- Related Link: https://bonproduction.net/

-

Nozomu Toyoshima

Photographer

Nozomu Toyoshima

Photographer

After Working At A Studio In Tokyo And As A Freelance Camera Assistant, He Has Been Working As A Photographer Since 2011.

- Related Link: http://toyoshimanozomu.com/

Tag

Share

Discussion

Index

Index

Archives

Recommend

Recommend

Recommend

Recommend

Recommend

-

{ Prototype }

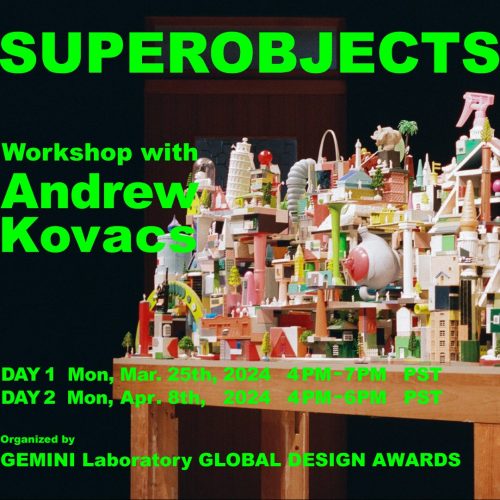

GEMINI Laboratory GLOBAL DESIGN AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCEMENT

GEMINI Laboratory GLOBAL DESIGN AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCEMENT

GEMINI Laboratory GLOBAL DESIGN AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCEMENT

-

{ Prototype }

A Dystopia In A World Freed From Death——Misato “GEMINI EXHIBITION: Debug Scene” Artist Interview 04

A Dystopia In A World Freed From Death——Misato “GEMINI EXHIBITION: Debug Scene” Artist Interview 04

A Dystopia In A World Freed From Death——Misato “GEMINI EXHIBITION: Debug Scene” Artist Interview 04

-

{ Special }

Virtual Visionaries: 『Empathetic AI identities』

Virtual Visionaries: 『Empathetic AI identities』

Virtual Visionaries: 『Empathetic AI identities』

-

{ Community }

Dr. Yukinori Kawae, Archaeologist/Egyptologist, Talks About The Essence Of Research, Including Concerns About The “God’s Perspective” Brought About By Technological Evolution.

Dr. Yukinori Kawae, Archaeologist/Egyptologist, Talks About The Essence Of Research, Including Concerns About The “God’s Perspective” Brought About By Technological Evolution.

Dr. Yukinori Kawae, Archaeologist/Egyptologist, Talks About The Essence Of Research, Including Concerns About The “God’s Perspective” Brought About By Technological Evolution.

-

{ Community }

DOMMUNE’s Naohiro Ukawa Talks About The Metaverse As The Third Summer Of Love Theory. How Will Experience Evolve In Virtual Space?

DOMMUNE’s Naohiro Ukawa Talks About The Metaverse As The Third Summer Of Love Theory. How Will Experience Evolve In Virtual Space?

DOMMUNE’s Naohiro Ukawa Talks About The Metaverse As The Third Summer Of Love Theory. How Will Experience Evolve In Virtual Space?

Hot topics

Hot topics

Hot topics

Hot topics

Hot topics

-

{ Prototype }

GEMINI Laboratory GLOBAL DESIGN AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCEMENT

GEMINI Laboratory GLOBAL DESIGN AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCEMENT

GEMINI Laboratory GLOBAL DESIGN AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCEMENT

-

{ Community }

Scenting the metaverse with olfactory futurist, Olivia Jezler

Scenting the metaverse with olfactory futurist, Olivia Jezler

Scenting the metaverse with olfactory futurist, Olivia Jezler

-

{ Community }

Architect Mark Foster Gage: Kitbashing opens up design possibilities

Architect Mark Foster Gage: Kitbashing opens up design possibilities

Architect Mark Foster Gage: Kitbashing opens up design possibilities

-

{ Community }

Fashion Historian Pamela Golban: Beyond the Fusion of Virtual and Physical

Fashion Historian Pamela Golban: Beyond the Fusion of Virtual and Physical

Fashion Historian Pamela Golban: Beyond the Fusion of Virtual and Physical

-

{ Community }

Ars Electronica’s Hideaki Ogawa on the Happy Relationship between Media Art and the City

Ars Electronica’s Hideaki Ogawa on the Happy Relationship between Media Art and the City

Ars Electronica’s Hideaki Ogawa on the Happy Relationship between Media Art and the City

-

{ Community }

Unlocking New Worlds: How Gaming is Leading Southeast Asia’s Journey into Web3

Unlocking New Worlds: How Gaming is Leading Southeast Asia’s Journey into Web3

Unlocking New Worlds: How Gaming is Leading Southeast Asia’s Journey into Web3

-

{ Community }

Tomihiro Kono, who also designs wigs for Björk, explores multiple areas of creativity, including 2D, 3D, and AR

Tomihiro Kono, who also designs wigs for Björk, explores multiple areas of creativity, including 2D, 3D, and AR

Tomihiro Kono, who also designs wigs for Björk, explores multiple areas of creativity, including 2D, 3D, and AR

Special

Special

Special

Special

Special

Featured articles spun from unique perspectives.

What Is

“mirror world”...

What Is

“mirror world”...

What Is

“mirror world”...

What Is

“mirror world”...

What Is

“mirror world”...

“mirror world”... What Is

“mirror world”... What Is

“mirror world”... What Is

“mirror world”... What Is

“mirror world”...

Go Down

Go Down

Go Down

Go Down

Go Down

The Rabbit

The Rabbit

The Rabbit

The Rabbit

The Rabbit

Hole!

Hole!

Hole!

Hole!

Hole!

Welcome To Wonderland! Would You Like To Participate In PROJECT GEMINI?